Finding the Wick Branch

A Florilegium of The Secret Garden, M.C. Escher, and John 15

In The Secret Garden, the young protagonist stumbles upon a long-sealed garden—closed off not by locks alone, but by grief and memory. The robin, a kind of trickster guide, leads her to the hidden door (“Shall we follow the deceptions of the thrush?”), and what she finds is not a fairytale paradise, but the tangled aftermath of lost love and neglect. Still, life remains. Through the nature-wise character Dickon, Mary learns to look closely—beyond appearances—to see what is still wick.

To say a branch is “wick” is to say it’s alive. Beneath the gray bark, sap still flows. It may look dead, but it remains connected to the root. And if it is connected, it can be healed.

This, of course, evokes John 15: “I am the vine, you are the branches… apart from me, you can do nothing.” The life of the branch depends entirely on its hidden communion with the vine. The vitality is not self-originating; it flows.

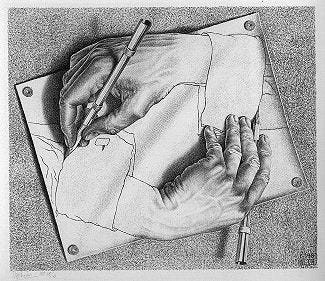

Now consider M.C. Escher. I love his prints. Drawing Hands is brilliant and mesmerizing. But in light of John 15, it becomes an uncanny foil. The two hands draw each other into existence—a clever visual paradox—but one that subtly reverses the Gospel’s premise. These hands are their own source. No vine. No root. Only a closed loop of self-creation.

Many of Escher’s works operate this way: infinite staircases, recursive worlds, shapes that fold in on themselves. They are elegant illusions of autonomy—forms that generate themselves from within. But unlike the wick branch, they are not alive. They are sterile marvels of design, not living things that grow.

So we’re left with two visions: the wick branch and the drawing hands. One lives because it draws life from something beyond itself. The other only appears to live, locked in a loop that cannot reach beyond itself. One speaks of regeneration. The other, recursion.

Both can be beautiful in their way. But only one can bear fruit.

Beautiful